Two hundred years have passed since British novelist Mary Shelley published Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus in 1818. Frankenstein contains the story of scientist Victor Frankenstein, who figured out the mysteries of life, and of the monster that he created by putting together parts from cadavers. Shelley’s novel has since inspired hundreds of works on this theme. The issues that it raises—including the rebellion of the created against its creator, the price to be paid for usurping the divine role of creating life, and the separation of sex from reproduction—have not gone out of date. On the contrary, they are becoming increasingly relevant in an age when technology is developing at a ferocious rate in areas such as artificial intelligence and stem-cell research. To mark the bicentennial of Frankenstein in 2018, this exhibition focuses on the issues that it raised, presenting the works of nine artists working on three subjects that connect with art at a fundamental level today: revival, the Anthropocene, and biopolitics. These works by artists from five different countries may be only a small sample, but they exemplify new issues relating to the artistic medium and to the historical and systematic aspects of art: biological entities as copyrighted material, sculptures formed from proteins, and land art as the origin of Anthropocene art. Bio-art is a trend that is flourishing at a global level. The exhibition presents just a fraction of the front line of that trend, but the works you see here are selected for deeper reasons than a perfunctory categorization of anything related to biotechnology or life as bio-art, or an attempt to impart a superficial understanding of the concept. It examines the significance of the specific medium chosen by each of the artists for its significance in today’s historical and social context, and also reviews the works from a contemporary perspective to explore how they incorporate connotations that further extend that significance. Frankenstein in 2018 attempts to provide hints for assessing the value of this new art at a time when the creation of life, once allegorical, is becoming increasingly real. It will have succeeded if it gives viewers even a small sense of such a future.

READ MORE

CLOSE

Pure Human, Tina Gorjanc, 2016-

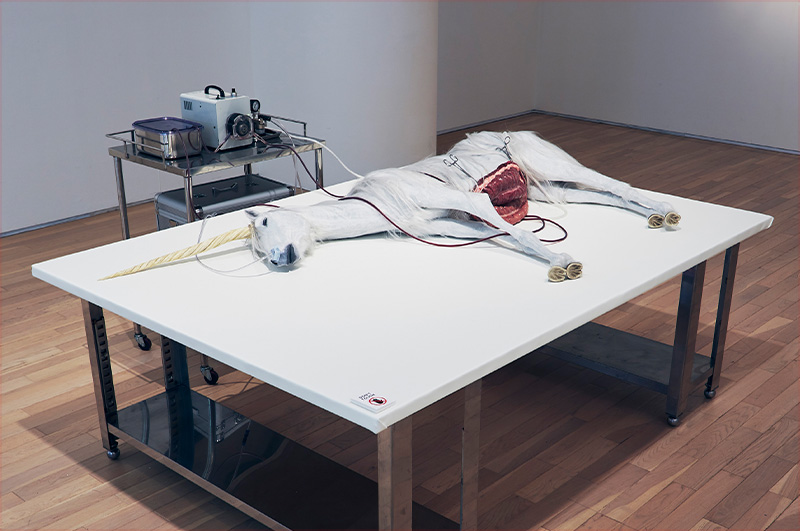

Revive a Unicorn, Mami Hirano, 2014-

Frankenstein’s monster was born by joining together parts from dead bodies, but the act of reviving fragments of the dead is a new theme that sets bio-art apart from conventional art. In ancient and medieval times, art on the theme of bringing the dead back to life concerned miracles or supernatural phenomena—such as the resurrection of Christ or Saigyo’s rite for recalling a soul— that were beyond the capabilities of mere man. Such art was no more than a metaphorical expression of a lesson that needed to be learned, or of anxieties faced in society. In contrast, at the beginning of the 19th century, Frankenstein no longer depicted revival as supernatural or miraculous. At the end of the 18th century, Italian physiologist Luigi Galvani had performed animal electricity experiments, sending electricity into the nerve cells of corpses and demonstrating that it caused legs or arms to move. These, and other experiments had overthrown the conventional perception of life, allowing the modern mechanistic view of life to begin to emerge, regarding living creatures as being capable of being reproduced and manipulated like other physical phenomena. Since the 1980s, the sudden development of genomics, and the emergence of stem cell technology and genome editing techniques have reinforced this perception, and it seems increasingly rational. The new technologies have also given artists tools for expressing ideas in ways that had once been impossible. Based on this context, the first chapter takes revival as its theme. Through the works of three artists, it examines the extent to which the use of media such as fragments of living organisms and immortal iPS cells can transform the concerns of artists, conventionally addressed to subjects such as life and death, the body, aesthetics, and individuality, and it considers what new meaning attaches to the symbolism of revival.

Pure Human

Pure Human is a speculative project presented in 2016 by London-based designer Tina Gorjanc, envisaging the use of stem cell technology to reproduce the skin of fashion genius Alexander McQueen so that it can be used as a material for clothing and accessories. The sample leather jacket has the look of human skin, with McQueen’s body shape, moles, freckles, and tattoos painstakingly recreated on pig skin. To create an actual product, the skin for producing the leather would be lab-grown from stem cells using DNA extracted from McQueen’s hair, which was incorporated into dresses in his 1992 Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims collection. The owner of one of those dresses has committed to making the hair available. This project, derided as Frankenstein-style fashion, represents a new fetishism in fashion produced by biotechnology, and focuses attention on the implications of wearing products of the deceased in a different form from that of actual body parts.

Revive a Unicorn

The dying unicorn stretched out in the exhibition space is Revive a Unicorn, created in 2014 by Mami Hirano, the youngest artist participating in the exhibition. The unicorn is a mythical beast, but Hirano created it piece by piece, including its skeleton, organs, blood vessels, and skin. The result is strikingly real. The theory of evolution may have smashed the validity of religious stories of divine creation of humanity, and relegated dragons, yokai, and other monsters to the realm of superstition, but Hirano nevertheless felt the need to revive such imaginary creatures. The unicorn that she is trying to bring back from the verge of death is a superb metaphor for the way that largely-disappeared premodern magic seems to have a growing chance of revival today, with contemporary science and technologies like synthetic biology and artificial intelligence becoming more and more like magic as they gain in sophistication and complexity.

Sugababe

Diemut Strebe’s Sugababe is based on the premise of bringing back to life the left ear that Gogh cut off. Strebe’s sculpture constructed from proteins is supplemented by a system that can simulate nerve impulses when you speak into the ear, then convert the impulses to sounds in real time. When exhibited at ZKM in Germany in 2014, famed linguist Noam Chomsky participated in a performance that involved him talking to Gogh’s ear. The video was broadcast by BBC, CNN, and other media, triggering worldwide interest. Lieuwe van Gogh, the great-great-grandson of Vincent’s brother contributed cartilage cells, and a descendent of Vincent’s mother provided mitochondrial DNA via a saliva sample. The Gogh ear was then produced by tissue-engineering, introducing the DNA into the cartilage cells. This results in a Frankenstein-like paradox, raising the question of whether a part of someone’s body synthesized using material provided by others—even if it uses cells that have the same DNA as the deceased—can still be said to belong to the original individual. It also shakes the concept of death, disputing its finality.

EXHIBITS

CLOSE

Why Not Hand Over a "Shelter" to Hermit Crabs?, Aki Inomata, 2009-

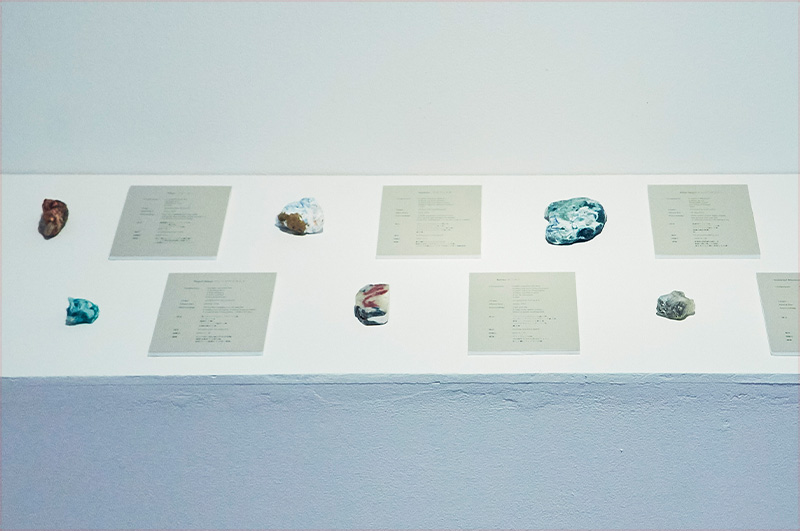

Everybody needs a rock, Sae Honda, 2016-

Tarred birds, Mark Dion, 2003-

The opening and closing scenes of Frankenstein are set on the ice near the north pole. The novel was written at a time when the ice symbolized the powerlessness of humanity, and nature was God’s creation. Since the industrial revolution, however, the development of science and technology, growing populations, and increased consumption of resources resulted in nature being exploited in order for humankind to efficiently and rapidly accumulate wealth, resulting in a situation where mineral resources and fossil fuels that had taken hundreds of millions of years to build up were running out after only a few centuries. In such circumstances, nature lost its mystique. Nature in pristine form had once been close at hand and easy to find, but today, atmospheric pollution (factory smokestacks and vehicle exhausts), marine pollution (tanker spills, plastic wastes, domestic and industrial sewage, agrochemicals), and radioactive pollution (nuclear weapons and power plant accidents) have taken their toll, so that finding unsullied nature has become virtually impossible. A great deal of Frankenstein’s polar icecap has already melted due to global warming, and its magnificence is waning. Paul Crutzen, one of the Nobel-winning scientists who enabled us to understand the ozone hole, pointed out early in the 2000s that human activities now had the capability to transform nature just as much as volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, earthquakes, and meteorites, and coined the term Anthropocene as the name for this new epoch in Earth’s history. The Anthropocene is considered to begin in the second half of the 18th century, at the time when Victor Frankenstein was supposedly engrossed in the creation of artificial life. The fact that he was portrayed as completely unmoved by the beautiful natural scenery suggests that the romanticist exaltation of the sublimity of a nature unbreachable by human activity was already in decline. This chapter takes the Anthropocene as its theme, examining, through the works of four artists, the decline of the concepts of nature and sublimity, and the relationship of that decline to contemporary art.

Glue Pour

Robert Smithson’s Glue Pour (1969) involved pouring orange industrial adhesive down a steep slope, mimicking lava with man-made material and caricaturing the abstract paintings of modernism. By using a highly toxic human artifact to erode nature, this work can also be seen as some of the earliest Anthropocene art, making nature impure and marking the decline of its sublimity.

December 1969

Vancouver, Canada

Exhibition print from original 126 format color transparency, printed 2018

12 x 12 in.

Collection of Holt/Smithson Foundation

© Holt/Smithson Foundation, licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Tarred birds

Mark Dion’s sculptures of tarred birds and x-ray photographs of birds with congenital malformations carry the implication that today’s polluted environment is the result of using science and technology to manipulate nature in order to increase the wealth of society. Fragments of white dolls in tar symbolize the over-reliance of humanity on sources of motive power such as coal and oil in modern society. At the same time, they are metaphors for our position, sandwiched between the positive and negative aspects of technologies such as regenerative medicine, nuclear power generation, and virtual currencies. Such developments may make our lives more convenient, but the more convenient they become, the greater the risk of destruction and ruin that they present.

Everybody needs a rock

Through works such as 4 fake fossils , Mark Dion had predicted that the mass-consumption of our civilization would leave its mark on the Earth’s geology. That prediction was validated in 2012, when a new form of mineral, named plastiglomerate and consisting of an agglomeration of melted plastic debris, volcanic rock, sand, and shells, was discovered on the Hawaii coast. Inspired by the discovery, Sae Honda began to create unique artificial gemstones by melting together plastics found at the roadside. A total of 60 billion tons of plastics are said to have been manufactured since the 1950s, an amount that is sufficient to package the whole planet. Honda regards her plastiglomerate as a secondary form of nature, a contemporary and distinctive mineral created through the activities of human beings, creatures that are covering the whole surface of the Earth. The rocks can also be interpreted as fossils from the Anthropocene.

Why Not Hand Over a "Shelter" to Hermit Crabs?

AKI INOMATA is perhaps one of the best-known artists of Anthropocene art, and has created a number of works that use creatures living in artificial environments to portray essentially human characteristics. Examples include Lines—Listening to the Growth Lines of Shellfish, a project for discerning changes to the environment pre- and post-3.11 by examining the growth lines of clamshells from Soma in Fukushima Prefecture, and girl, girl, girl, ..., a project where bagworms constructed homes from branded fashion clothing. Her signature Why Not Hand Over a "Shelter" to Hermit Crabs? series includes works where the homes given to crabs are 3D-printed models of cities. The crabs move from city to city, New York to Tokyo, then Tokyo to Paris, perhaps representing refugees, or raising issues of identity in a globalized world. At the same time, the hermit crabs that accept and carry around man-made shells are a marvelous metaphor for the Anthropocene—an epoch were humans overwhelm other forms of life, exposing both to the risk of extinction.

EXHIBITS

CLOSE

Stranger Visions, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, 2012-

BLP-2000B: DNA Black List Printer, BCL, 2018-

Frankenstein’s monster suffered from hunger, faced a coarse diet for long periods, and was coldly discriminated against for being different from those around him. He offered to move far away, but his creator, afraid of the monster propagating, killed his partner. The monster eventually took revenge before killing himself. This tragic story can be seen as depicting the state of poverty that affected so many in Britain, and as a criticism of the Principle of Population published by classical economist Thomas Robert Malthus in 1798. The Malthusian theory of population was an attempt to counter the writings of William Godwin, who was the father of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. Shelley was critical of the eugenics that lay behind the population control advocated by Malthus as a strategy to overcome poverty and food shortages—including emigration, birth control, and starvation for the poverty-stricken—and responded to Malthus through her depiction of Frankenstein’s monster. The influence of Malthusian concerns can be seen in the first British census, conducted in 1801, but the information was used for welfare purposes, providing statistics about the lives of the population, including birth rates, death rates, levels of health, lifespan, and conditions that affect these figures. This marked the beginning of the change to a modern political system that administers the lives of the population through centralized management of information—what philosopher Michel Foucault called biopolitics—instead of through the medieval approach of threatening to kill anyone who does not obey. However, the clear difference between the biopolitics of the modern era and the biopolitics that we see today is that from 1970 onwards the collection and utilization of biological information has been driven by the development and commercialization of biotechnology, particularly genetic engineering. Today, DNA and other biological information extracted from proteins and cells is handled by databases appropriate for commercial use, retaining a closer grip on the health, abilities, and appearances of the individuals who were the source of the information. In this third chapter, the focus is turned on this sort of contemporary biopolitics, examining the works of Heather Dewey-Hagborg and BCL to gain hints about the future of art and politics from biological information and matter at the micro level.

Stranger Visions

Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions project uses DNA extracted from discarded cigarette butts and human hair to generate images of the faces of people who left such traces behind. The project began in 2012 as a reminder that the DNA we unknowingly scatter around can reveal not just information about our appearance, such as gender, ancestry, and eye and hair colors, but also information about our risk of succumbing to various illnesses. Sometimes it can even expose personal information that the individual was unaware of. The technology has since been incorporated into a DNA Snapshot crimefighting tool developed with the support of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security that is now in practical use. Dewey-Hagborg’s project initially warned of the biopolitics of a future society where DNA is used for surveillance and there are impulses towards genetic determinism. Now it is a warning that such a society is already becoming a reality.

BLP-2000B: DNA Black List Printer

In contrast to Stranger Visions, which questions our being managed by the technology that we developed, BCL’s BLP-2000B: DNA Black List Printer (2018) asks the fundamental question of whether it is actually possible for humans to control science and technology. This work lists up and prints DNA sequences containing viral nucleic acid sequences banned by bioengineering companies because synthesizing them risks triggering a pandemic. The emergence of technologies such as genome editing that enable living matter to be easily and inexpensively edited opens up the way for anyone at all to potentially contribute to progress in life sciences. However, at the same time, it raises the possibility of triggering new types of bio-terror. This work spotlights the dilemma that the technology presents, prompting debate on the question of what sort of future we should choose.

EXHIBITS

CLOSE

Frankenstein in 2018:

Bio-art throws light on art, science, and society today

Term: 2018.9.7 (Fri) - 10.14(sun) 11:00 - 20:00

Venue: EYE OF GYRE /GYRE 3F

Artists: Robert Smithson,Diemut Strebe,Tina Gorjanc,Heather Dewey-Hagborg,Mark Dion,BCL,AKI INOMATA,Sae Honda,Mami Hirano

Organizer: GYRE / Sgùrr Dearg Institute for Sociology of the

Arts Supervision: Takayo Iida (Director, Sgùrr Dearg Institute for Sociology of the Arts)

Curation: Yohsuke Takahashi (Curator, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa)

Graphic design: Rikako Nagashima (village®) Construction: Suga Art Studio

Cooperation: Holt/Smithson Foundation, Ronald Feldman Gallery, FRIDMAN GALLERY, SCAI THE BATHHOUSE,

MAHO KUBOTA GALLERY, HiRAO INC. Contact: GYRE (03-3498-6990)