Until now, I have generally exhibited my works so that each room contains only works of the same series. Doing that keeps the focus on what is being shown and simplifies what the viewer perceives. For this exhibition, however, each room is shared by works of more than one series, and the overall configuration has several such spaces linked together. The space is not particularly large, but I thought it would be interesting to create a more expansive experience so that viewers progressing through the venue encounter dissimilar works one after another, allowing each of the different stories and concepts to combine.

I’ve been working on the PixCell series for close to twenty years, but most of the other works here are the result of new experiments. The Dune series is one example. Dune was an attempt to reproduce images of dune-like landscapes using physical material to create paintings rather than using video. When several different types of paints and media are mixed in certain proportions and poured onto a canvas lying on the floor, differences in mass—heavy or light—and differences in particle size mean that some components flow further than others, which results in a variety of patterns and shapes. And if you mix viscous materials with others that are not viscous, they separate when the paint dries, which produces wrinkles. Particularly in areas where the paint has formed a thick layer, it will split when the surface dries, producing lightning bolt cracks and leaving completely unexpected surface patterns.

In 2019, I produced a video installation entitled Tornscape for the Throughout Time: The Sense of Beauty exhibition at Nijo-jo Castle in Kyoto. For that project I collaborated with programmer Ryo Shiraki to transform landscapes and weather using physics simulations, generating what looked like aerial photography of the results. I then turned that into a video work based on a theme taken from Hojoki (An Account of My Hut), which was written by Kamo no Chomei about 800 years ago. His writings took the form of reportage covering a series of disasters that hit Kyoto—including a horrific fire, famine, epidemics, and earthquakes—describing matter-of-factly how people went on living despite the terrible afflictions that beset them. The sense of being in circumstances where life and death recur seems to depict the Buddhist concept of impermanence.

Today, we still face troubles like those depicted in Hojoki, including massive disasters triggered by earthquakes and the coronavirus pandemic of 2020. It has been striking to see that people really do go on living their lives despite the calamities. I wanted to capture that worldview by painting it with real paints, as in Dune, rather than with a computer simulation, because the physical properties of the paint would give a richer expression. That sort of difference is the main reason why I continue to create sculpture. It has a strength that comes from the texture being conveyed directly from the materials, and from the experience of physically sensing the work within a space. In the works I produced for this exhibition, Oracle, I put an emphasis on things that can be physically felt or received to a greater extent.

Today, we still face troubles like those depicted in Hojoki, including massive disasters triggered by earthquakes and the coronavirus pandemic of 2020. It has been striking to see that people really do go on living their lives despite the calamities. I wanted to capture that worldview by painting it with real paints, as in Dune, rather than with a computer simulation, because the physical properties of the paint would give a richer expression. That sort of difference is the main reason why I continue to create sculpture. It has a strength that comes from the texture being conveyed directly from the materials, and from the experience of physically sensing the work within a space. In the works I produced for this exhibition, Oracle, I put an emphasis on things that can be physically felt or received to a greater extent.

Some of my work involves the stage for performing arts. Dancers always follow the choreographer’s directions, but there are times when the choreographer creates detailed movement sequences for the dancers, and other times when the choreographer shares the story or concept with the dancers and leaves the dancers to interpret the instructions in their own way. My approach to sculpture is more like the latter. Rather than dancers, I work with paints and all sorts of other materials, thinking about how I can take advantage of the breadth of physical properties that the materials possess, and how I can convey those properties to people’s senses. I want to know where, and in what sort of form the work will eventually connect with people’s senses. When mixing the paints and other materials, I keep that in mind as I build my image of the form the work will take.

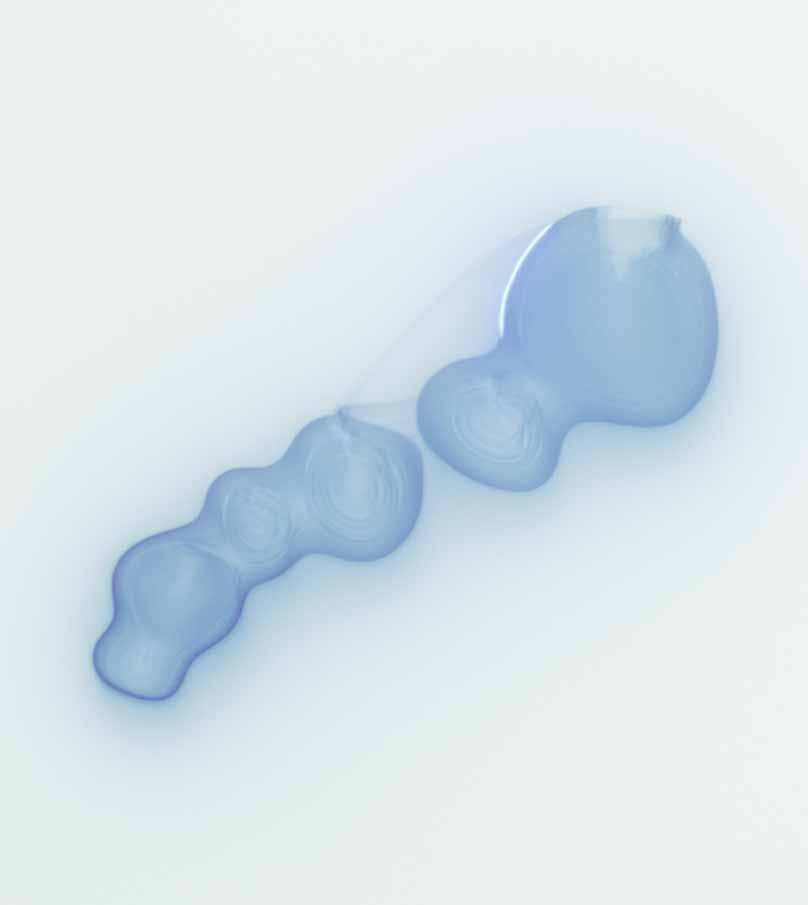

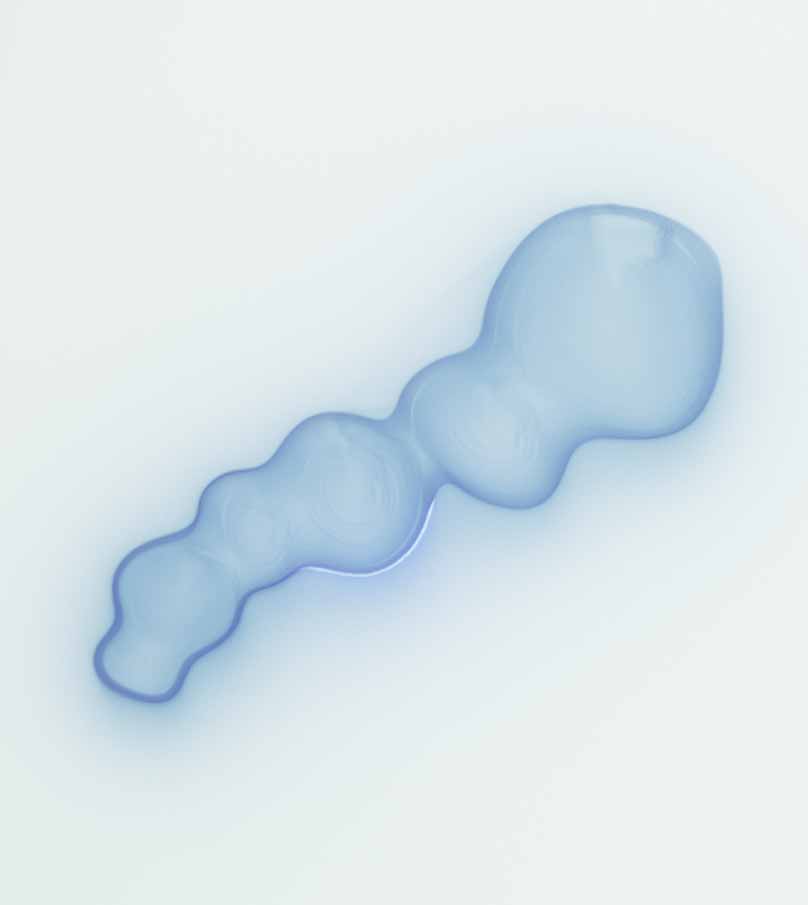

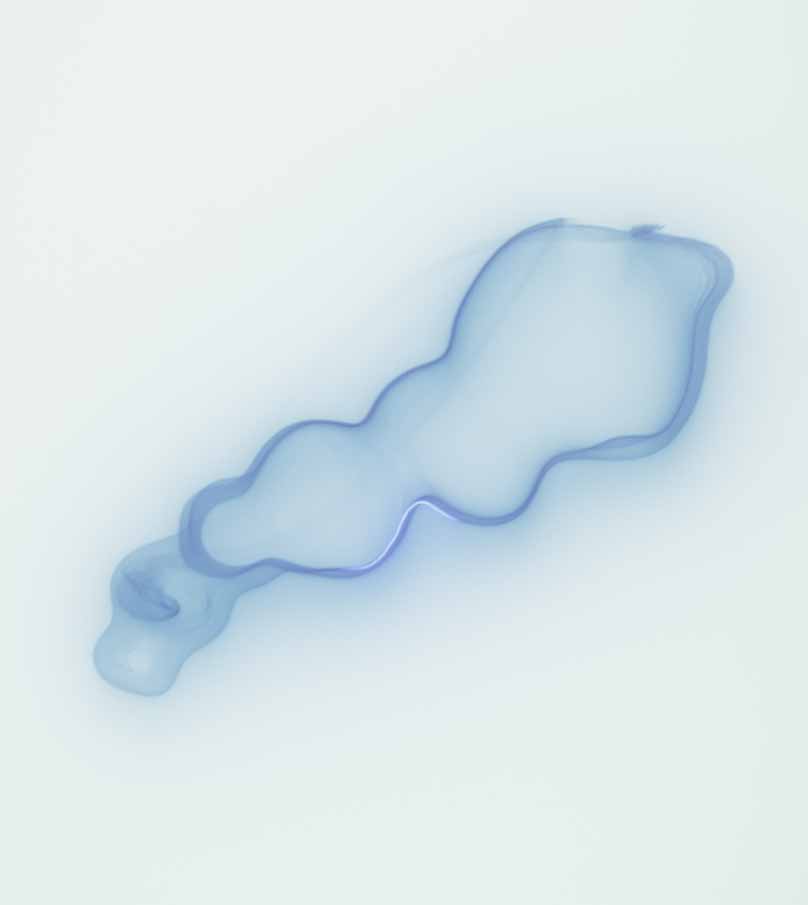

Over the past few years, I have been creating and building up a collection of 3D models that take plant seeds and ovules that as their motif. Blue Seed is a series of works in which their shapes appear one after another. Rather than a continuous sequence of scan lines, I use UV lasers directed at a board covered with special pigments. The laser traces the outlines of cross-sections through the seeds or ovules, and the pigment reacts to the ultraviolet light by turning blue for a short period, maybe twenty or thirty seconds. This produces what appears to be a three-dimensional image, which soon fades away.

It’s fascinating to imagine the power that seeds and ovules pack within their shapes. Once they absorb water and the temperature changes, they put up shoots, and before long they are growing into a large tree of some sort. They are truly the source of life. I find them mystical.

Ever since I first harbored the ambition to become a sculptor, the sorts of sculptures that survive through long periods of history have attracted me. I am particularly impressed by the amazing religious art that has continued to develop since medieval times.

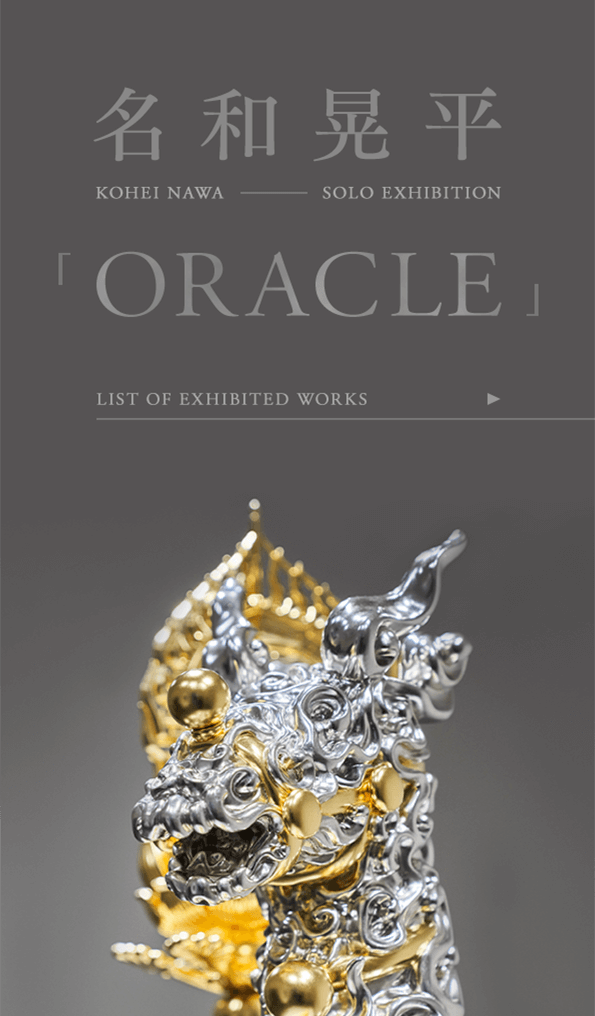

People say that today’s capitalist world makes it difficult for such works to emerge, but if you look at Kyoto, there are still many artists and artisans who are still active, including Buddhist statue sculptors, lacquer workers and gold leaf specialists, and superb skills and knowledge are still being passed down. Their methodology is the complete opposite of the mass production approach that has been churning out products since the industrial revolution. Their methods can produce works that will still be around hundreds of years later or even a thousand years later. The fact that such methods are unchanged and are still viable today demands great respect. Trans-Sacred Deer (g/p_cloud_agyo) was produced with the assistance of many such Kyoto artisans.

The way that Buddhist statues are made has of course changed over time, incorporating the revolutionary technologies of each age to produce awesome statues. Thinking about what sort of methods we should be using now to create a work like that which can last through history, I made the decision to form the work using a computer. Once I had a 3D model formed in that way, the next step was to go through the various processes at the artisans’ workshops, beginning with woodcarving, and followed by lacquering and a metal leaf finish. Through this approach, I created a sculpture that blends together the new and the traditional.

I chose "Oracle" as the title for this solo exhibition, but there is no deep significance behind the choice.

Trans-Sacred Deer (g/p_cloud_agyo) takes the Kamakura-Period sculpture Kasuga Shinroku Shari Zushi as its motif. I started work on this project last year (2019). It is made in the image of a sacred deer formed from a cloud that appeared to people lost in fog, leading them to safety. While I was working on it, the coronavirus began to spread around the world, and the pandemic has coincided with this exhibition.

During the pandemic, many people are searching for answers, but answers seem to be difficult to find. In both medicine and politics, even the top experts are finding it difficult to reliably point to the approach that we need to take. It seems as though we are in circumstances where we can only pray for help, relying on divine intervention. To some extent, the exhibition title reflects that situation.

I chose "Oracle" as the title for this solo exhibition, but there is no deep significance behind the choice.

Trans-Sacred Deer (g/p_cloud_agyo) takes the Kamakura-Period sculpture Kasuga Shinroku Shari Zushi as its motif. I started work on this project last year (2019). It is made in the image of a sacred deer formed from a cloud that appeared to people lost in fog, leading them to safety. While I was working on it, the coronavirus began to spread around the world, and the pandemic has coincided with this exhibition.

During the pandemic, many people are searching for answers, but answers seem to be difficult to find. In both medicine and politics, even the top experts are finding it difficult to reliably point to the approach that we need to take. It seems as though we are in circumstances where we can only pray for help, relying on divine intervention. To some extent, the exhibition title reflects that situation.

This year is the Centennial Celebration of the Establishment of Meiji Jingu. I have been taking part in the year-long Centennial Festival, and as one of the commemorative events, Ho/Oh went on display at the southern gate in front of Meiji Jingu’s main shrine. The installation coincides with the Oracle opening, and it is on display until November 3, 2020. It’s marvelous to be able to present a solo exhibition on Omotesando at the same time that this work is displayed as part of the festival to mark Meiji Jingu’s centennial.

The centennial provides an opportunity to think about how the restoration of Emperor Meiji provided the foundation for the modernization of Japan that underlies contemporary society in Tokyo and in Japan as a whole. I’m pleased to be able to celebrate this milestone. I hope that it will result in people recalling that Omotesando was designed to be the main avenue leading to Meiji Jingu, and that they will take the time to visit the shrine.

In planning this exhibition, I was not thinking of selecting works that would be appropriate for the pandemic. Despite that, because the works in the Rhythm series incorporate a number of spheres, they seem to have the appearance of viruses. That is a demonstration of how people’s perceptions have changed over the year. In fact, I began experimenting with this series the year before the pandemic emerged, and I had no particular intention of representing viruses. Nevertheless, I am interested in the fact that the works gained the appearance of something else. Art is a medium in which that sort of thing occurs.

When a work is not verbal, and when it gives no hints of an individual’s emotions and has no traces of manipulation by someone’s hands, the physical properties and the created form itself stand out more than the artistic intent. As a result, it facilitates very neutral perceptions, as if looking at a natural object. I am convinced that creating contact points and entry points of this sort can lead to a situation in which the viewer of the work finds something, or something commences within the viewer himself or herself.

I’ve often said that I am not focused on self-expression. I find no satisfaction in creating art for self-expression or self-fulfillment. Today, everyone has avenues for expressing themselves, so I feel that artists in particular no longer have the need to seek out such opportunities. Instead, my desire is to produce new expressions by becoming a filter for re-interpreting something, or becoming a mirror that reflects something. The instincts and senses of an artist can become triggers or tears in the fabric that instigate transformations in the way that people see or sense something. Those moments of transformation are what is amazing about art, and art with the potential to do that is the sort of art that I want to create.

For the moment, I just want to keep on producing new works. I stay focused on art that is universal. That’s what I want to leave behind. That’s my objective. I am not at all motivated to create works that address individual social issues, or that oppose particular systems. I tend to think that the very idea of interpreting art as an expression of an opinion about something is an oversimplification of the logic. I want to keep my focus on things that are more universal.

Sculptor Kohei Nawa is director of Sandwich Inc. and professor at Kyoto University of the Arts. Born in 1975 in Osaka, Japan and based in Kyoto, in 2003, Nawa received the first PhD in Fine Art/Sculpture awarded by Kyoto City University of Arts. Focusing on the surface “skin” of sculpture as an interface connecting to the senses, Nawa began his PixCell series in 2002 based on the concept of the cell, symbolizing the information age. Adopting a flexible interpretation of the meaning of sculpture, he produces perceptual experiences that reveal the physical properties of materials to the viewer through works addressing themes related to life and the cosmos and to artistic sensibility and technology, including Direction, in which he produces paintings using gravity, Force, in which silicone oil pours down through a space, Biomatrix, in which bubbles and grids emerge on a liquid surface, and Foam, in which bubbles form enormous volumes. VESSEL, a performance work produced in conjunction with Belgo-French choreographer and dancer Damian Jalet, has been presented around the world since its premiere in 2015. Recently, Nawa has also worked on architectural projects, including the art pavilion Kohtei completed in 2016 within the Shinshoji Zen Museum and Gardens in Fukuyama, Hiroshima. In 2018, his sculpture Throne was exhibited under the Pyramid at the Musée du Louvre in Paris, France. Nawa is based at Sandwich, the creative platform that he founded in the Fushimi area of Kyoto.

SANDWICH is a creative platform founded by Kohei Nawa in 2009 in a renovated sandwich factory near the Uji River in the Fushimi area of Kyoto. In addition to studio, office, and workshop spaces, it has a residential area to provide accommodation. It functions as a space where creators from diverse fields, including architects, designers, engineers, choreographers, and dancers, can gather together to collaborate on a range of projects and become involved in production under Nawa’s direction.

- Kohei Nawa solo exhibition Oracle

- Dates

- Friday, October 23,

2020 ‒ Sunday,

January 31, 2021 - Hours

- 11:00 ‒ 20:00

- Venue

- GYRE GALLERY,

5-10-1 Jingumae,

Shibuya-ku, Tokyo - Contact

- +81-3-3498-6990

- Cooperation

- SCAI THE BATHHOUSE,

GRAND MARBLE,

HiRAO INC, Sandwich Inc. - Press

Contact - Sandwich Inc.|

45-1 Fujinoki-cho,

Mukaijima, Fushimi-ku,

Kyoto 612-8132 Japan

T&F_+81-75-468-8211

Contact: Misuzu Wakaki |

office@sandwich-cpca.net

HiRAO INC|

1-11-11 #608 Jingumae,

Shibuya-ku,

Tokyo 150-0001 Japan

T_+81-3-5771-8808

F_+81-3-5410-8858

Contact: Seichiro Mifune |

mifune@hirao-inc.com